WHAT THE DICKENS!

A look at the making of A Christmas Carol.

Commentary by Kevin Lane Dearinger for The Lexington Theatre Company

“Marley was dead. To begin with.”

So starts A Christmas Carol.

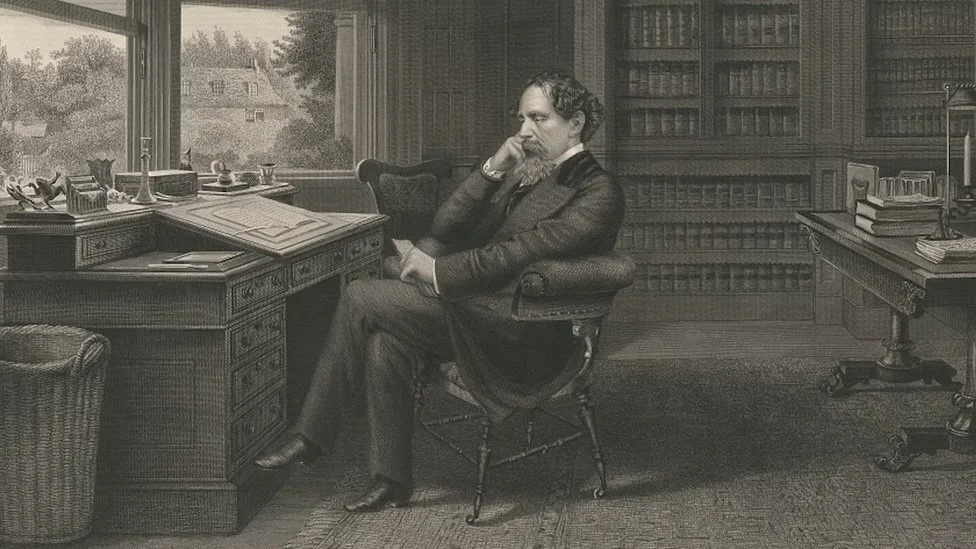

Charles Dickens knew how to craft an opening line.

“It was the best of times...” “Chapter One: I Am Born.”

Never repeat that old slander that he was paid by the word.

Dickens was an artist.

Despite his love of comic hyperbole, he was also a realist. In his way. Although Christmas ghost stories had long been an English tradition, Dickens was interested in life, not the supernatural.

Yet, he had his own ghosts.

When A Christmas Carol was published in 1843, Dickens was already famous, already successful, and only thirty-one years old. He and his wife Catherine had four children with one on the way. They would eventually have ten.

To the British public, Dickens was a celebrity, a jolly fellow, a family man, and practically a saint.

He was also restless.

In 1842, he dragged his bewildered wife away from their young family and set out to investigate the great democratic experiment across the Atlantic. Dickens had admired what he heard of America, and America already loved him.

Even if they devoured pirated editions of his novels for which he went unpaid.

In Boston, he was hailed as a hero, and the neatness of New England impressed him. He found New York too busy, Philadelphia too boring, and Washington just disgusting. He was appalled that the noble members of Congress soaked the carpets with tobacco juice. The sight of enslaved human beings enraged him. “Spittoons, slavery, and senators,” he wrote. “All of them evil.” He traveled west by steamboat, admiring Louisville and Cincinnati, but did not drop down on Lexington. He began to lecture his hosts on the need for international copyright laws. The visit turned sour. Bitterly.

Dickens needed money. He always needed more money. A growing family, a bigger house, and his generosity with his friends meant that money was spent almost as fast as he could make it. He was the sort who always picked up the check

As soon as he was back in England, Dicken swiftly completed his unflattering American Notes. He did everything swiftly, exhausting friends and family with his energy. Ask his wife.

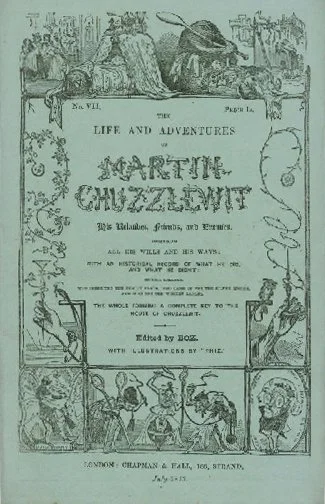

Still needing money, he began a new novel in serial form. For the first time in his career, his work did not seem to catch on. Martin Chuzzlewit is as full of memorable characters and plot as any of his stories, but it wasn’t until Dickens sent Martin to America that sales picked up. On both sides of the Atlantic, readers followed the hero’s disenchantment with the flawed paradise.

Sales picked up.

But Dickens needed still more money.

He feared poverty.

An old ghost for Charles Dickens.

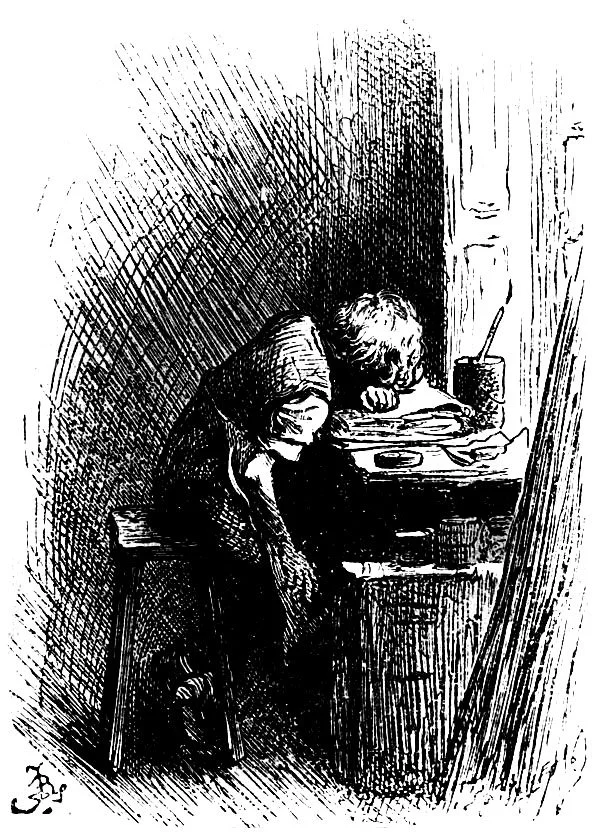

His childhood had been far from idyllic. A quiet, dreaming boy, his life with his parents and siblings in Camden Town—where the Cratchits, including Tiny Tim, would later live—was cruelly shattered when his father landed in debtor’s prison. Following the custom of the time, the family went to live with him behind bars, except young Charles, who was sent to work long hours in a factory. Child labor. He could never speak of that time without crying.

All those powerless children in his novels—Oliver Twist, Paul Dombey, Little Nell—were the product of his old sorrow. An unhappy childhood also haunts Scrooge.

Dickens knew from experience that a lack of money could destroy his world. Again.

A touch of Scrooge?

Perhaps

He wrote A Christmas Carol in six weeks, got it to the publisher in time for holiday shopping, and sold out the first edition in three weeks.

He made some money.

Except, of course, in America, although this would get straightened out eventually. All was forgiven. On both sides.

And Scrooge was among us.

He always has been.

Scrooge, we are told, has no “fancy,” no imagination. Lack of imagination is Estella’s explanation for having “no heart” in Great Expectations. The heartless educators Mr. Grandgrind and Mr. McChokemchild in Hard Times work viciously to eradicate imagination in their students, replacing “fancy” with facts, cold and hard. Like cash.

Think “Scrooge.”

Again, abused children. Dicken’s ghosts.

“Want” and “Hunger,” the miserable children revealed by the Ghost of Christmas Present.

Dickens loved the theatre and considered becoming an actor. He had an audition for the Drury Lane Theatre but caught cold and missed the appointment. He wrote several early plays and even contributed lyrics to a song. (Sad to say, they are wretched.) As an adult, he wrote about the theatre with great affection—Mr. Wopsle’s foolish Hamlet in Great Expectations, the Infant Phenomenon and the lovable Crummles family in Nicholas Nickleby. As Mr. Sleary, manager of a traveling circus in Hard Times, explains, “People mutht be amuthed.”

Dickens also acted in private theatricals and gave sold-out readings of selections of his work. One of the most popular was always A Christmas Carol.

Of course, his stories ended up on stage. Not that he got paid. Still.

A theatrical adaptation of A Christmas Carol appeared in London within a year of the book’s publication.

Scrooge took center stage and stayed there.

On stage, in silent and then talking movies on the big screen and on television. Alistair Sim. George C. Scott. Jim Carrey. Patrick Stewart. Michael Caine with the Muppets. Animation Scrooges: Mr. Magoo. Scrooge McDuck. Even Monty Burns. And Scrooge’s first cousin: the Grinch.

A movie musical. With Albert Finney. With dancing in the street of London. “Thank You Very Much.”

Then back on stage. A very big stage. Madison Square Garden in New York, for a holiday spectacular, with the talents of the best of Broadway.

And that is, in fact, the version that is coming to the Opera House with The Lexington Theatre Company.

Thank you, Charles Dickens.

The Lexington Theatre Company’s production of A Christmas Carol, the Musical, plays the Lexington Opera House for six festive performances, November 20-23. Curtain time on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday evening at 7:30, Sunday at 6:30, with Saturday and Sunday matinees at 1:00.

Kevin Lane Dearinger is obviously a retired English teacher. Also a retired actor and singer. He now writes. His published works include four theatre histories, six volumes of poetry, several plays, and two memoirs, Bad Sex in Kentucky and On Stage with Bette Davis: Inside the Fabulous Flop of Miss Moffat. His theatrical career took him to Broadway, on tour across the United States, Canada, and Japan, and to many of the best regional theatres in the country. When he was very young, he sang in a Broadway tribute to director Joshua Logan at the Imperial Theatre; his last professional performance was in a Broadway tribute to Stephen Sondheim at the New Amsterdam. He is proud of his Actors Equity Pension and counts among his blessings the privilege of sitting in on rehearsals with The Lexington Theatre Company. He is currently attempting to write a history of the Lexington Opera House. He is excited.